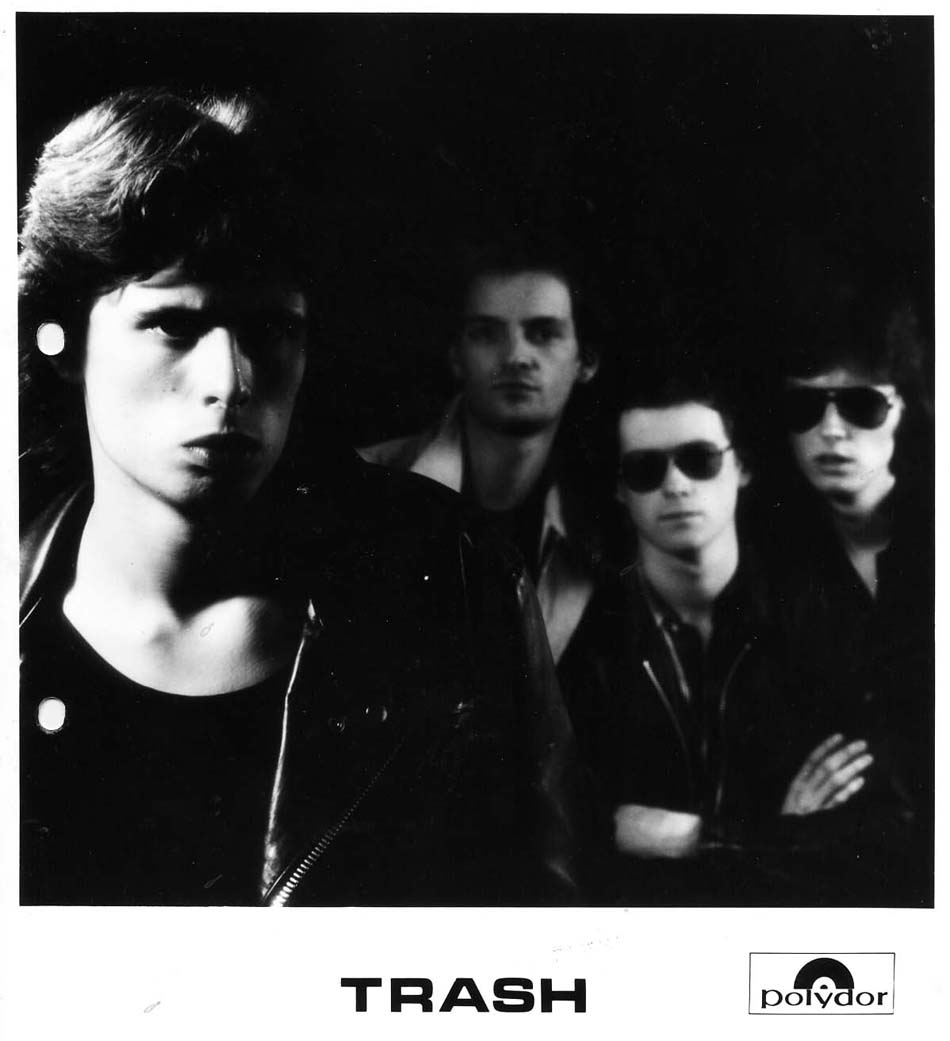

TRASH INTERVIEW

WITH SIMON WRIGHT and TONY BELLEKOM FROM TRASH (6th June and 2nd July 2014 - via email)

THE GIBBON: I'd just like to start off by saying I’ve thoroughly enjoyed the This Is Complete Trash! CD, and laud your decision not to clutter it up with “dodgy demos” etc. How did the CD come about? How did you decide what was left out, and were there any of your own songs that didn’t make the cut?

SIMON WRIGHT: Ever since I set up the Trash website in 2007 I thought it would be good to release our collection of rotting cassettes in digital form. Track selection was a fairly democratic process. I came up with an initial selection which Mick and Keith then edited. It's not as though we had endless archives to chose from so the selection was pretty obvious. We always used to play a lot of covers live, so I was conscious of not including too many on the CD. Our breathless versions of Let's Spend The Night Together, Pills, The Last Time, Anyway Anyhow Anywhere, Can't Explain, Editions Of You, Rescue Me and Coming After Me will have to remain legendary. Of our own songs I'm Not Eating would have been good if recorded by a 12 year old girl. Our country and western number just should not have existed.

THE GIBBON: In the interview, Mick Brophy describes the band’s music as “1977 Pop”, and also refers to “new wave bands”. No mention of punk. Also, I see on the Bored Teenagers site there's a flyer with the statement “Trash - are not a punk band”. What was behind this conscious decision to distance yourselves from punk as such? Had Trash ever been a punk band, or had it just gotten stale and boring? If so, what were the symptoms of it being stale and boring?

SIMON: We never thought of ourselves as punks. We were fast and simple rock'n'roll at time when it was briefly fashionable. Mick and I were massive music fans, heavily into the likes of the Who, Stones, Kinks, Flamin' Goovies, New York Dolls, Dr Feelgood. We saw people like The Clash and the Pistols as building on this musical legacy. I knew Paul and Glen from the Pistols well enough to talk to at gigs and I knew they were huge music fans. There was no chance of us refuting all music created pre-1977.

THE GIBBON: Both Mick and Tony sound dead posh. Were you all posh?

ANTONY BELLEKOM: Well this is an easy one to dispel! I had a brilliant childhood on a council estate in Somerset and was the first in my family to go to university.

SIMON: We were massively middle class at a time when it was unfashionable to be so. We met at college. Mick and I were the first from our families to go to university. Mick's family were from Reading, mine lived in Surrey, Keith was from Birmingham. Tony was from the West Country (he went on to a successful career at the BBC). We were always very upfront about our backgrounds. We could never see the point in pretending to be something that we were not, as a result there was not much mystery around us. We got the piss taken out of us by other bands – I think the Slits were particularly cutting, calling us the Homepride Boys (it was during our white boiler suit phase).

THE GIBBON: I believe the band was formed in the wake of the Pistols playing at National College of Food Technology in Weybridge. Were you all students there? What were the Pistols like? And did you or any of the other band members have any serious musical ambitions before this event?

SIMON: We were all studying at the National College of Food Technology, a small and bizarre college situated on St George's Hill, Weybridge amongst some of the most expensive real-estate in the UK. We had Cliff Richard and Tom Jones for neighbours. So we had to make our own entertainment. There was a hall, the college owned a small PA and there were various amps and drumkits knocking about. Mick was Social Secretary, responsible for organising dances, I was his assistant. The Pistols turned up unbooked and unbidden one Saturday night and virtually cleared the hall. Except for Mick, Jane and me who all thought they were wonderful. We went to as many Pistols gigs as we could after that – I used to see them every Tuesday at the 100 Club. I was at the front the night they played Ron Watts Punk Rock Festival there and so my picture crops up in various pics from the night. Jane was there that night, but didn't want to risk front of stage. We also went to the Screen On The Green Allnighter and sat next to Siousxie at the height of her sartorial daftness (swastika armband, tits out for the lads).

ANTONY: They were actually booked by me for the princely sum of £10, so their unannounced appearance is sadly apocryphal.

On the night they were accompanied by a group of very early fans/supporters including one Vivienne Westwood. I was in the tiny dressing room before as they were about to go on stage and, with long hair in those days, John asked me if I had a comb…rapidly adding “No, I don’t suppose you would have..”. For those collectors of trivia, they were using an HH PA recently purchased from Cat Stevens. They also had a logo painted on of crossed pistols, that clearly didn’t survive long, but McLaren recycled for Adam & The Ants. It was a life changing gig...

The thing about the college was that an awful lot of students there never had any real interest in food technology, but it seemed like a fairly comfortable place to be at a time when getting a grant to study was still possible. It meant that you had plenty of time to devote to more interesting things!

For whatever reason, it seemed to attract a lot of people who had an interest in music. I was Social Sec for a while, as was another year-mate, who combined his last year at university with working at Albion Management, looking after The Stranglers. Like me, he has managed to spend his entire working life around music.

On top of that the college was close to West London, which at the time was awash with brilliant venues. In writing about punk/new wave its easy to see it just as a response to the excesses of prog-rock. The reality was that pub rock came first and that probably made punk’s entry a little easier. You could literally catch 4 or 5 bands a night with ease.

None of the venues was “comfortable”, but concentrated on the music (and making a profit I guess). Almost without exception they have disappeared. I was visiting Decca, the other day and as I came out from West Kensington tube, I went to the pub next door. It was newly refurbished and none of the staff I spoke to could remember its day as The Nashville, probably the best of the venues on that side of London.

I booked Ducks Deluxe for the college – a huge personal favorite - and a country-tinged outfit called Flip City, led by one Elvis Costello, or Declam McManus as he still was then. Complete with suede shirts….

THE GIBBON: The group started as a quintet. Did you play many shows before Jane Wimble [co-vocalist] left, and why did she leave?

SIMON: I think we only did a handful of shows with Jane. She was great onstage – Rescue Me really scorched when she sang it. I think it all got too serious for her and she wanted to concentrate on her studies.

THE GIBBON: What was Polydor like as a label? What kind of deal did they offer you? Judging by the fact that Priorities was also released in Germany and Italy, it seems they had faith in the band.

SIMON: Our deal was two singles with the option on an album. I think the advance was maybe £1000, which we used to buy a PA. If Polydor had any faith in us they kept it well hidden. Their key acts were The Jam and Sham 69, both of whom had assertive management and long-tem deals. Only the Press Officer Chris Bohn was remotely useful, and he left.

ANTONY: In those days if you were a band, being signed seemed like the difference between success and failure. The truth is they were - and are - businesses that need to make a profit and signing and dropping bands is a way of life, not much difference to Cadbury and chocolate bars, if you like. There was a lot of enthusiasm for the band at the outset and Trash was signed at the same time as The Jolt. Whatever Trash’s shortcomings, there was clearly enough going on in the band to make it a worthwhile signing. This happened at the time when all the main labels wanted at least two new punk/new wave signings; none of them wanted to miss out. So, however fresh, new and exciting the new music movement was, it was almost instantly turned into a commodity exercise by the labels, much the same as every musical development before and after. Trash was particularly unlucky in that Polydor was itself sold around that time and as is always the case, new owners like to have a clear out. The music world now is so different, it hardly bears comparison. With digital music and the internet a new act has to ask itself why it needs a label in the first place…. But that’s a longer story.

THE GIBBON: Did having a production company (Sara Bee) help or not? What was the deal with that exactly?

SIMON: We signed to Polydor indirectly, via Sara Bee. Sara Bee was Clive Selwood's company. Clive was an industry veteran – he had run Elektra in the UK and was John Peel's manager. It was Clive's daughter who saw us in action and recommended that Clive check us out.

THE GIBBON: What was it like recording with Shel Talmy and Nigel Gray?

SIMON: Talmy was great. Blind as a bat. Mick went round to his flat near Marble Arch which had which had an immensely plush white carpet completely covered in fag burns where Shel had missed the ashtray. We were in awe of Talmy because of all those amazing Who and Kinks singles he'd produced. His engineer did most of the work in the studio but where Shel came into his own was pre-production. He took the demo tape of NNERVOUS to pieces and completely re-arranged it to bring out the hooks.

Nigel Gray in comparison did very little to the songs. We just set up in the studio and then played live. I think the only overdubs were vocals. However he got a terrific sound, the best studio sound we ever achieved

THE GIBBON: How many recording sessions did you do other than the ones on the CD?

SIMON: A few duff ones in demo studios in and around Reading with borderline incompetent engineers and squeaky drum pedals. We also used to record rehearsals onto cassette. Somewhere there must be a copy of Mick's rock-opera Carrots! We actually played that live a few times towards the end of the band – like a mini-Tommy.

THE GIBBON: Some of the reviews you got were pretty damning (“not much originality in either concept of execution”, “identipunk as politely regurgitated by cultured mouths”). Were they right? Is there a case for the defence, m'lud?

SIMON: We weren't punks – we just weren't very good. We were not particularly original but we were getting more original as we played more gigs.

THE GIBBON: The CD liner notes describe Wire as “startling”. In what way?

SIMON: They (appeared) indifferent to musical history and tradition – you could never imagine them jamming on Johnny B Goode. Being unpopular didn't seem to bother them. Plus they played songs that were a minute or less. The only musical influence their bass player would admit to was Boz Scaggs (I think he was winding me up).

THE GIBBON: You also mentioned playing with the Lurkers a lot. Did you get friendly with them? Any stories?

SIMON: No.

THE GIBBON: What bands did you rate during the time, either bands then doing the rounds or bands that had influenced you?

SIMON: We played with Johnny Curious and The Strangers in Welwyn Garden City, they were good. Also a really ageing bunch of musos called Slack Alice. Their singer (Alice, obviously) enticed me on stage to join their encore of Honky Tonk Women. It was the only time I was ever drunk on stage and I enjoyed it greatly.

THE GIBBON: What was Priorities actually about?

SIMON: Mick wrote it. The lyrics were railing about the expectation that we would all finish college and then take up 'good' jobs working in food factories. It was all looking a bit Dull. Mick actually did help run a cake factory for a while and I still work in the food industry today (albeit in chocolate, which is Not Dull).

THE GIBBON: Can you tell me about the ice cream bucket incident?

SIMON: I was working at Lyons Maid Ice Cream in Greenford. Every Friday night we were allowed to take ice cream home – I used to go for the Cornettos. In order to get the ice-cream from Greenford to our communal slum in Reading without the ice cream melting we would add dry ice to the carton (which meant you always got a seat on the train as your luggage was gently steaming). One Friday night we had a gig so I brought the ice creams along. I thought we could use the leftover dry ice in our stage act. We agreed that at the climax of our last number our faithful roadie John Parry would drop the dry ice into bucket of water and the stage would fill with smoke. Unfortunately John dropped the whole cardboard box into the bucket which exploded sending a mixture of dry ice, freezing water and ice-cream over the stage. We all promptly fell over. End of set.

THE GIBBON: How much money do you think you made from Trash? And did Polydor ever pay you any royalties?

SIMON: I don't remember getting anything beyond the initial advance. I suspect any royalties were eaten up by recording costs.

ANTHONY: Trash had the grand sum of £1,000 as advances and this was spent on a van. I think its fair to say that the band must have lost overall. Certainly, we were subsidizing pretty well everything. I borrowed enough off my parents to buy Mick’s Guild guitar. I really must pay them back.

THE GIBBON: Do any copies of the In On All The Secrets fanzine sill exist, or have they all been lost?

SIMON: I have a complete set, they are locked securely in a Swiss bank vault waiting for the day when In On All The Secrets is used on the soundtrack to Despicable Me 6 and we all become very rich and all our artifacts are sought after by Japanese dealers.

THE GIBBON: This may sound a like a stupid question, but how did everyone react when Polydor dropped you?

SIMON: Dropped is way too dramatic a term for what happened. How I remember it is after it became apparent that NNNERVOUS was not going to do anything I said to Mick I am really fed up of living in abject squalor on no money, let's knock it on the head. He had apparently been thinking along similar lines but didn't want to be the first one to say anything. So Mick and Keith went off to work in the food industry, I went back to my degree (eventually – it took 10 years!) and drummer-at-the–time Simon Butler-Smith looked for another band with which to drum.

THE GIBBON: After the failed Quadrophenia attempt, did the band split in between that and recording the Nigel Gray demo? When you say the “studio saw no future in them”, what did you mean exactly?

SIMON: We were totally split when I blagged the Quadrophenia audition – I had to take the afternoon off work to schlep up to the Electric Ballroom for the auditions (whatever did happen to Crosscut Saw?). Ditto the Nigel Gray session.

THE GIBBON: Any disastrous / funny / amazing Trash moments you'd like to tell me about?

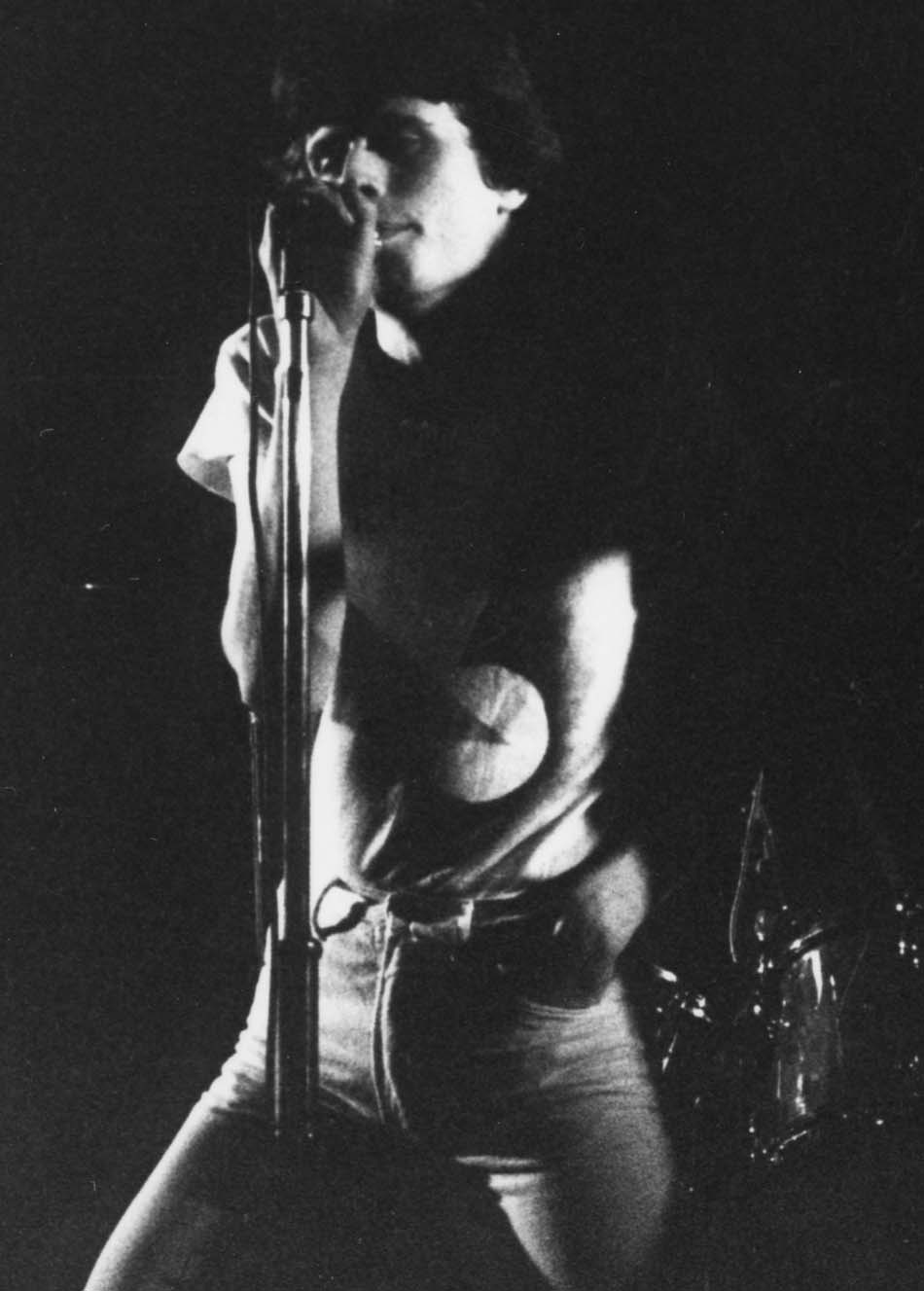

SIMON: At no point in our time together did we have a clue. We had groupies that we didn't sleep with because we did not realise that was what you did. Our preferred rock'n'roll intoxicant was a pint of mild (because it was cheap). We rehearsed in a vicarage. We were massively uncool. And yet every so often we played a gig that was so great it left us all grinning for days afterwards.

ANTONY: The Trash van was pretty representative of our haphazard approach. We spent the advance on it, but it wasn’t really enough. It was bought second hand from a stationery company in Reading, but we couldn’t afford to repaint it, so this band with “attitude” used to appear in this little old van that promoted typewriter ribbons.

THE GIBBON: Did you keep in touch with any of the other band members after the group folded?

SIMON: All of them. Even our manager

THE GIBBON: What musical ventures did you partake in after Trash split?

SIMON: I sat in with Mick's next band The Cheaters a few times. They got a deal with EMI and were big in Norway. My speciality was Louie Louie. We also had a band together called The Young Lords for one afternoon where I sang You're Looking Fine (Dave Davies) at a festival in Manchester.

ANTONY: I have been extremely fortunate to have spent most of my working life around music, starting by running venues. I had more than 25 years in radio, including the job of a lifetime in starting 6 Music for the BBC. Currently, I’m working with the BRIT awards on a project to bring young people into music – The Big Music Project. I’m also working with what’s left of EMI on looking at how they can use their archive, going back to the 1890s, in new ways.

THE GIBBON: What are you best memories of you time with Trash?

SIMON: It was great fun until it wasn't.

ANTONY: Trash started as a group of friends with a shared interest in music. Despite everything we are still in touch! Did we think we would ever make it “big”? I don’t know, but it seemed like an adventure. There’s nothing better than the buzz after a good gig and we had a few of those on the way.

THE GIBBON: Finally, what did you think of punk at the time, and what do you think of it now? What is year zero or just rock's last hurrah? And did it REALLY change anything?

SIMON: In 1976 I thought the music scene in London was fantastic. I was going out most nights and seeing lots of loud, fast and funny groups. In 1977 I was buying some great singles. That was it for me – live music and 45s. Once people started to make albums and Xandra Rhodes started selling punk dresses – no. Most people you saw at Pistols gigs in 76 had long hair and wore flared trousers cos that's what music fans wore. When the punk look started emerging it got less interesting.

Today I still love my punk singles. Loud fast music – if you hear Pretty Vacant or Complete Control on Radio 6 today they are great sounding rock'n'roll songs.The only LPs I still listen to from that era are by The Heartbreakers and The Only Ones – interestingly both groups composed of experienced musicians who were picked up and assimilated by punk without being punks.

Where I think punk made a big difference was in changing the means of production. Small labels, bands doing it themselves, people putting on their own gigs and publishing their own magazines. I see the reverberations of this seismic shift today in music, in publishing, in art...even in food.

I did think punk had killed off prog-rock and flared trousers. How wrong I was…

Power pop also rans. They struggled on into late 1978 when, as The Duds, they auditioned for a part in Quadrophenia. They didn't get the job.

ANTONY: I think I always had broad musical taste and was enjoying the Ramones before the Pistols came along. Equally, I enjoyed some folk rock and, dare I say it, Genesis too. Today I think its positively cool to play stuff across a whole range of genres and the arrival of the iPod meant we all became collectors and could set off on our own musical journeys.

At the time punk was great and I have never forgotten just how powerful it was and some of the great bands that were around. And I have never forgotten some of the rubbish acts to…

Musically, I think it remains important in its own right, both in terms of the tracks from that era and from the current generation of artists. If it has significance beyond being another era of good music, it is that it has given more artists and audiences the right to try something new, to take risks and to not to be dismissive of the unexpected or uncomfortable.

You can add stuff and make comments/corrections by emailing me at:

THE GIBBON: COMMENTS